“Man is first animated by invisible solicitations.”

In December of 1940, a little more than two years before he created The Little Prince on American soil and four years before he disappeared over North Africa never to return, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry began writing Letter to a Hostage (public library) while waiting in Portugal for admission into the United States, having just escaped his war-torn French homeland — a poignant meditation on the atrocities the World War was inflicting at the scale of the human soul, exploring questions of identity, belonging, empathy, and the life of the spirit amidst death.

In December of 1940, a little more than two years before he created The Little Prince on American soil and four years before he disappeared over North Africa never to return, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry began writing Letter to a Hostage (public library) while waiting in Portugal for admission into the United States, having just escaped his war-torn French homeland — a poignant meditation on the atrocities the World War was inflicting at the scale of the human soul, exploring questions of identity, belonging, empathy, and the life of the spirit amidst death.

One of the most timelessly moving sections of the book, both for its stand-alone wisdom and for its evident legacy as a sandbox for the ideas the beloved author later included in The Little Prince — home, solitude, the stars, the sustenance of the spirit — is the second chapter, written while Saint-Exupéry was traveling aboard the crowded ship that took him from Lisbon to New York:

I lived three years in the Sahara. I also, like so many others, have been gripped by its spell. Anyone who has known life in the Sahara, its appearance of solitude and desolation, still mourns those years as the happiest of his life. The words “nostalgia for sand, nostalgia for solitude, nostalgia for space” are only figures of speech, and explain nothing. But for the first time, on board a ship seething with people crowded upon one another, I seemed to understand the desert.

Saint-Exupéry contemplates the psychology of boredom which, far from the creative force Susan Sontag believed it to be, takes on a wholly different meaning in the desert:

There, one perpetually bathes in the conditions for sheer boredom. And yet invisible divinities build up a net of directions, slopes and signs, a secret and living frame. No more uniformity. Everything takes up a definite position. Even one silence is unlike another silence.

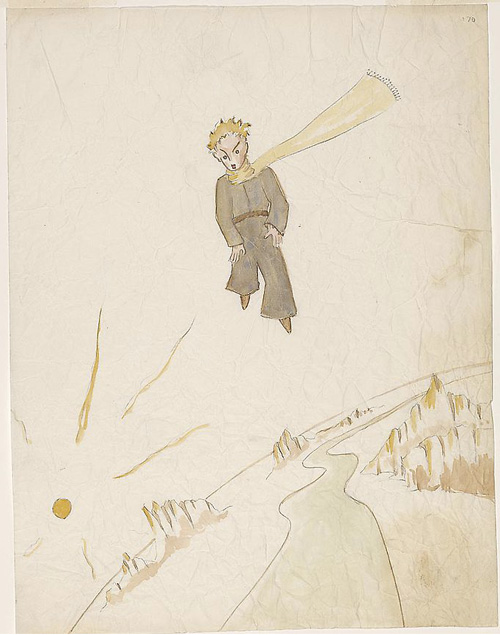

Original watercolor for The Little Prince by Saint-Exupéry. Click image for more.

He reflects on the Sahara’s peculiar place in the cultural history of silence:

There is a silence of peace, when the tribes are reconciled, when the evening once more brings its coolness, and it seems as if one had furled the sails and taken up moorings in a quiet harbor.

There is silence of the noon, when the sun suspends all thought and movement. There is a false silence when the north wind has dropped, and the appearance of insects, drawn away like pollen from their inner oasis, announces the eastern storm, carrier of sand. There is silence of intrigue, when one knows that a distant tribe is brooding. There is a silence of mystery, when the Arabs join up in their intricate cabals. There is a tense silence when the messenger is slow to return. A sharp silence when, at night, you hold your breath to listen. A melancholic silence when you remember those you love.

He considers how the vastness of the desert anchors one to a sense of belonging and pulls that inner wholeness apart at the same time:

Everything is polarized. Each star shows a real direction. They are all Magi’s stars. They all serve their own God. This one marks a distant well, difficult to reach. And the distance to that well weighs like a rampart. That one denotes the direction of a dried-up well. And the star itself looks dry. And the space between the star and the dried well does not lessen. The other star is a sign-post to the unknown oasis which nomads have praised in songs, but which dissent forbids you. And the sand between you and the oasis is a lawn in a fairy tale. That other one shows the direction of a white city of the South, which seems as delicious as a fruit to munch. Another points to the sea. Lastly this desert is magnetized from afar by two unreal poles: a childhood home, remaining alive in the memory. A friend we know nothing about, except that he exists.

So you feel strained and enlivened by the field of forces which attract or repel you, entreat or resist you. There you are, well-founded, well-determined, well-established in the center of cardinal directions.

And as the desert offers no tangible riches, as there is nothing to see or hear in the desert, one is compelled to acknowledge, since the inner life, far from falling asleep, is fortified, that man is first animated by invisible solicitations. Man is ruled by Spirit. In the desert I am worth what my divinities are worth.

What beautiful symmetry between this meditation and Saint-Exupéry’s most famous line from The Little Prince: “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

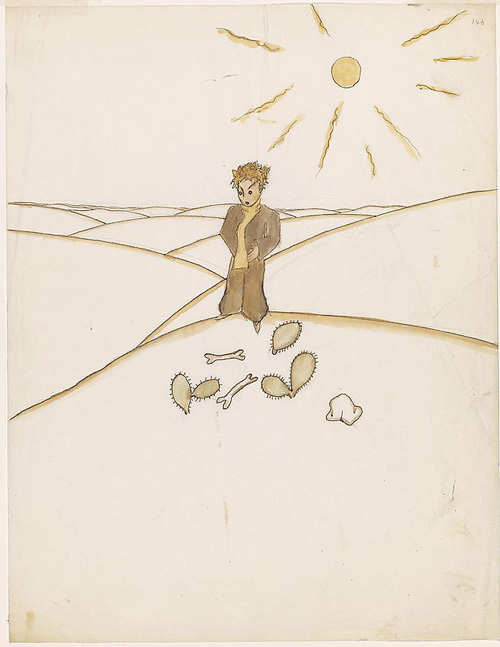

Original watercolor for The Little Prince by Saint-Exupéry. Click image for more.

Saint-Exupéry, who opens the chapter by observing that “the essential is that somewhere there remains the relics of one’s existence,” returns to the complexities of home and belonging:

France … was for me neither an abstract divinity, nor a historian’s concept, but a real flesh on which I depended, a network of links governing me, a mass of poles directing the inclinations of my heart. I needed to feel those I wanted to direct me more reliable and steady than myself. To know where to return. To be able to exist.

[…]

The Sahara may be more lively than a capital, and the most crowded city is deserted if the essential poles of life lose their magnetism.

Small as it may be, Letter to a Hostage is a monumental read and the most direct surviving glimpse of Saint-Exupéry’s boundless mind and spirit. Complement it with his original watercolors for The Little Prince, which exude a great deal of the Sahara sensibility he so cherished.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.